THE GRAPHIC OEUVRE

Joachim Dunkel belonged to the group of sculptors who are also passionate draftsmen. Only in rare cases are among the sheets sketches and preliminary studies for sculpture. In addition to the extensive corpus of so-called sculptural drawings in the narrower sense, there is an equally extensive body of narrative drawings, sometimes conceived in cycles, on which the draftsman worked for years.

The works on paper include nearly 100 woodcuts or printing blocks, which are available in paper prints by the artist's hand. Lithographs and etchings were created as part of Dunkel's teaching activities at the West Berlin Hochschule der Künste in the Visual Communication Department. These works from the years 1978 and 1985-88 have not yet been catalogued.

Figure and group

In the drawings we encounter the most diverse instruments and materials: pencils and colored pencils as well as the ballpoint pen, felt-tip pen, the pen in all its variations and the brush. Since the 1980s, the artist increasingly loved to use these means in combination and to set expressive colorful accents.

No figure, no scene solidifies within Dunkel's defined outlines. Rather, everything depicted remains pulsating in a state of suspension that can hardly be described. The draftsman renounces a certainty that would also lull the viewer into security. What appears to be an indication of an anatomical detail is always in reality an impulsive stroke or a number of such movement strokes. Primarily the transitory is thereby emphasized. And the form, detaching itself from the object, becomes free to express the soulful and spiritual, which belongs to the figure depicted, but at the same time refers back to the artist. This identification causes a more intense, more profound appeal to the viewer than any immovably made "objective" statement.

Mythology and fiction

The earliest mythological figure to appear in Dunkel's work is the bull-man Minotaur, whom he probably became acquainted with through Picasso in the 1950s, but who he then made his main hero, as it were, far beyond Picasso and in his very own way. He drew him in the most diverse, often quite freely invented situations - as a perpetrator as well as a victim. He treated the mythological figures Centaur and Pan just as freely, as well as the events surrounding Daphne, Actaeon, Marsyas, Orpheus, Paris, Adonis, Europa with the Bull, Hector, and material from the Troy complex.

Without specific ties to archaic, ancient, or post-ancient representational traditions, he invented hybrid creatures and creatures of pure fiction and composed them into vivid groups.

Scene and theme

Cycles of "Reineke Fuchs," "A Midsummer Night's Dream," "Macbeth," "Don Quixote," "La Belle et la Bête," "Chevalier de Florian," and Afghan fairy tales bear witness to Dunkel's love of drawing, which drew inspiration from epic, novel, and drama.

From the tradition he chose preferentially the death theme. Keywords are, for example, knights, death and the devil; death and the girl; the dance of death; the blood court. Dunkel exemplified the fight with a fatal outcome on the ritual of the bullfight on his numerous sheets to the "Death in the afternoon" .

Within the biblical tradition, the draftsman was preoccupied with the following topoi: Fall of Man and Expulsion from Paradise, Golgotha, Resurrection, Fall from Hell, Esther and Salome.

Since 1976 he has created landscape drawings and nature pieces exclusively plein-air in the French Jura. The depictions of horses and riders form a further complex of works. The number of animal studies based on nature occupies only a marginal place in Dunkel's oeuvre of drawings.

Woodcut/engraving

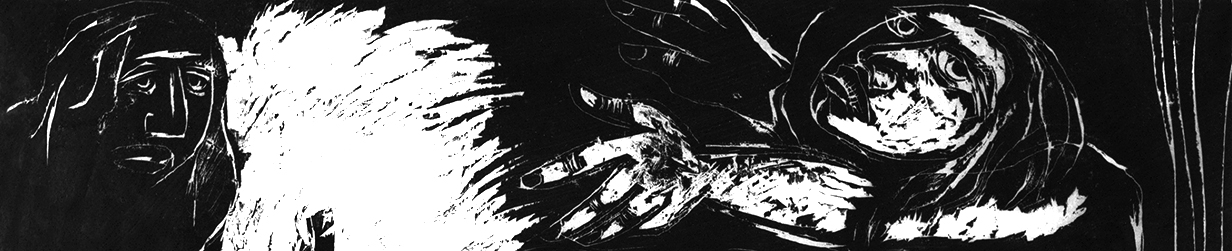

In Joachim Dunkel's oeuvre, the woodcuts occupy a special position. Created only in the years 1948-49 and 1991-99, their immediate force and expressive compactness, which sometimes has something almost threatening, is astonishing. On sheets of often almost mighty format, crowded representations develop, reduced to concise, yet always representational forms, to which the striking black-and-white contrast peculiar to the medium lends a suggestive power. It is characteristic that the settings of the scenes play no role, or at most an extremely minor one, limited to hints. In this way, the sculptor, the artist who "speaks" primarily through his figures, who thinks in figures and concentrates entirely on their posture and gestures, comes into his own.

Motifs of the nearly 50 early wooden sticks: Variété and circus, carnival and mask, fantasy animal and rider, male and female single figure, couple figure, scenes from the Bible. Motifs of the nearly 50 late woodblocks: Reineke fox, Hubertus stag, dance of death, death in the afternoon (bullfight), female figure, scenes of Orpheus, Marsyas, Actaeon, Daphne, Adonis, Hector.